Building an Innovation Ecosystem

The venture arm of the CSP needs to be aware of these ongoing tasks and projects. Today, CSP VCs are pulled in two conflicting directions. On one side, they are judged on financial performance against their non-corporate VC peers. On the other hand, they are asked to support the CSPs business direction. In order to support this seeding activity, CSP VCs need to allocate budget and staff to small seed investments in very early stage startups. Staff working in this area need to be compensated based on the vitality of the seedling stream, not on traditional VC metrics. It should be noted that top-tier VCs have such seeding programs today. Unfortunately, those top-tier VCs will not make any kind of investment in a startup focused on selling to CSPs as a result of current CSP behavior around startups. Once CSPs adopt the kind of activity recommended here, top-tier VCs can be expected to change their behavior and start supporting the innovation ecosystem too.

Seeding an Innovation Ecosystem

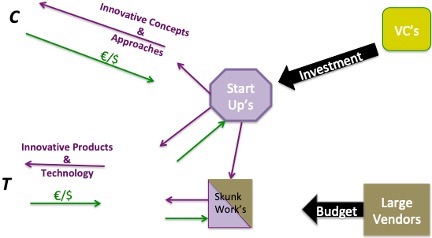

These CSP funding streams go to support two kinds of organizations: pure startups and skunk works in large vendors that combine with startups. Startups are the engine that drives the kind of S/W innovation that CSPs need. But not all startups will have good ideas, and not all those with good ideas will be able to deliver. Thus, a portfolio approach is needed. This means the use of relatively small amounts of money to explore and test is the best way forward. Once a future direction is determined, it’s essential to build a portfolio and use a portfolio process to filter out the good ones and grow them.

The most famous skunk works was in Ford Motor company. A small group of staff came to the conclusion that there was a market for a kind of car that company management would never approve. They got together in a remote corner and, with no budget and while working on their approved tasks, designed and built a prototype of the car they had in mind. A senior executive discovered the skunk works, embraced the vision, and maneuvered it through corporate resistance. That executive was Lee Iacocca, and the car was the Mustang.

This story is instructive, because a successful skunk works is not enough. There needs to be a champion to bring even a very successful project across the finish line to full realization. So, in addition to all the other steps described here, there have to be people placed within the organization with the right personal network and credibility to carry successful projects into implementation.

Figure 2. Innovation Generation

Because skunk works are housed in large organizations, they can sometimes play a valuable role in delivery and support. These skunk works are likely to recognize and understand the value of particular innovations but, because of the corporate culture of large organizations, they are likely to have difficulty in coming up with the fundamental technical inventions without seeding by startups.

By pairing a large vendor skunk works with a startup, it is sometimes possible to get a better result in delivering the early stage projects. In the later stages, it may also provide a faster way to move successful products and services into production.

Large organizations are not monolithic. Some in a large vendor will support this kind of activity. Others will oppose it. Opposition may take many forms, including NIH (not invented here). Or may take the more subtle forms of sowing FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt), or practicing EEE (extend, embrace, extinguish). Some will base their resistance on protecting legacy products. Others may act out of a felt need to protect their ‘empire.’ Here again, the champion has to work to counteract these. To do so, the champion can best function with the support of the CEO and even a member or two of the board of directors. But the Mustang case shows that even without that support, a good champion can be effective.