Designing Pervasive Mobile Networks

Through Multi-Modal Architecture

By: Grant Kirkwood

Pervasive mobile networks have become a central objective in modern telecommunications strategy, yet the term is often misunderstood. In practice, pervasive connectivity is not defined by the size

of a coverage footprint or the availability of a single access technology. It is defined by the ability to maintain usable, predictable connectivity as users, devices, and applications move across

environments, infrastructures, and operating conditions. As mobility becomes foundational to how organizations operate, the distinction between coverage and continuity has become increasingly

important.

Pervasive mobile networks have become a central objective in modern telecommunications strategy, yet the term is often misunderstood. In practice, pervasive connectivity is not defined by the size

of a coverage footprint or the availability of a single access technology. It is defined by the ability to maintain usable, predictable connectivity as users, devices, and applications move across

environments, infrastructures, and operating conditions. As mobility becomes foundational to how organizations operate, the distinction between coverage and continuity has become increasingly

important.

Public-sector agencies, private enterprises, and multinational organizations now operate in conditions where connectivity must persist across indoor and outdoor environments, remote locations,

and mobile or temporary operations. These environments challenge traditional network assumptions. Infrastructure may be limited, degraded, or unavailable. Network conditions can change rapidly.

Users and systems often have little tolerance for disruption. In this context, pervasive mobile networks are less about extending reach and more about designing systems that adapt to variability.

From Coverage Expansion to Continuity

Meeting this requirement demands a shift in how networks are conceived and built. Traditional network designs have often relied on a hierarchy of primary and backup connectivity, where one access method is favored and others remain idle until failure. This model struggles to support modern mobility, where variability is constant and resilience depends on treating all available connectivity as active and contributory rather than secondary or exceptional. Pervasive mobile networks are instead emerging from multi-modal architectures that integrate multiple access layers into a unified, intelligent system.For decades, network investment focused on expanding coverage. Success was measured by signal strength, geographic reach, and peak performance under ideal conditions. While these efforts significantly improved access, they did not fully address the realities of mobility. Coverage maps do not account for what happens when users move between networks, enter infrastructure-constrained environments, or operate in locations where terrestrial connectivity is intermittent or unavailable.

Modern applications expose these limitations quickly. Many assume continuous connectivity by default, even as users transition between buildings, vehicles, and outdoor environments. When networks are designed in isolation, these transitions often introduce latency, dropped sessions, or degraded performance. The result is a user experience that feels fragile despite nominal coverage.

Rethinking Network Design Assumptions

Pervasive mobile networks shift the focus from static availability to dynamic continuity. The objective is not to eliminate differences between access technologies, but to manage those

differences in a way that preserves application performance and operational stability. This reframes connectivity as a systems challenge rather than a purely radio or transport problem.

Multi-Modal Architecture in Practice

Multi-modal connectivity has emerged as a practical response to the complexity of modern mobility. Rather than relying on a single access method to meet all requirements, multi-modal

architectures combine multiple connectivity options and allow them to complement one another. Each access type brings distinct strengths and limitations shaped by geography, infrastructure,

spectrum, and deployment constraints.

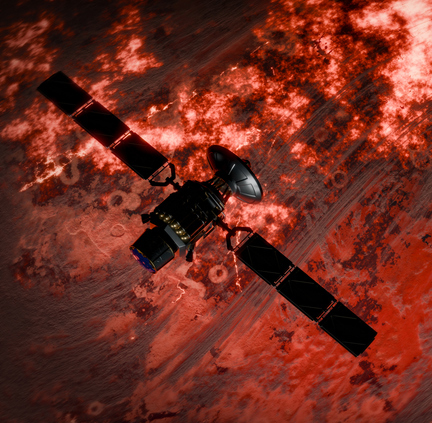

Terrestrial cellular networks provide wide-area mobility and scalability. Private wireless networks offer greater control and predictability in localized environments. Indoor wireless

technologies remain essential for dense, enclosed spaces. Fixed broadband and fiber deliver capacity and stability where infrastructure exists. Non-terrestrial connectivity extends reach into

locations where traditional access is impractical or unavailable.

The effectiveness of a multi-modal approach does not come from any individual layer. It comes from orchestration. In more advanced architectures, connectivity is not