Across the Middle Mile: How BEAD is

Rewriting the Rules of America’s Connectivity

For all the innovation we’ve seen in the last decade, internet access in the US is still largely governed by one thing: geography. The nation stretches nearly 3,000 miles from coast to coast and is home to some of the most challenging and diverse terrain on the planet, from the bayous of Louisiana to the volcanic ridges of the Pacific Northwest. Even in densely populated regions like California and Washington State, there are bays, river crossings, forests, and protected lands that make affordable, reliable, and meaningful connectivity to underserved areas a persistent challenge.

More than a fifth of households in the US still lack access to broadband, in part, due to the sheer cost of bringing connectivity to these remote or difficult-to-access communities. The result is a “digital divide” that is as literal as it is figurative – how can high-speed broadband reach these communities across such vast terrain?

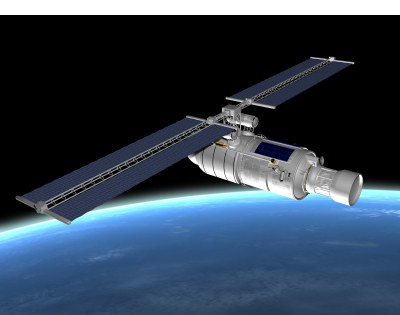

These stretches of geography that lie between the core internet infrastructure or fiber points of presence and local access networks make up what’s known as the “middle mile” – the link between the nation's internet backbone and the communities that serve the end-users that need it. The “last mile” is the infrastructure that carries this connectivity into homes, businesses, and other buildings, where fiber optic cables are considered the gold standard. For the most part, trenching to lay cables is sufficient for the middle mile, too, but it can be slow or cost-prohibitive – especially over longer distances – and what happens when geography makes digging up the ground unfeasible? Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites offer an alternative, but the setup requires a lot of upfront investment, and the distance data needs to travel makes latency an ongoing challenge in addition to the lack of capacity to serve many users simultaneously with high throughput. Real-time data exchange, edge-based processing, and AI will soon form the basis of our economy – and those technologies are not compatible with low bandwidth and high latency. So, what’s the answer?

Meeting the Connectivity Challenge with BEAD

The Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program’s mission is simple: to connect all of America. When the $42.5 billion program was announced, it was a predominantly fiber-first initiative as that was seen as the surest way to get high-speed connectivity where it was needed. But technology evolves, and now BEAD is evolving with it.

Earlier this year, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), which oversees BEAD, rewrote the rules of its flagship broadband program. What began as a fiber-focused initiative is now, by policy design, technology-agnostic. In other words, states have been advised to use every qualifying technology at their disposal to bridge the middle mile and connect the last mile, with scoring now heavily favouring cost and speed of deployment. In what the federal government is calling “The Benefit of the Bargain”, every US state and territory has been instructed to design their networks considering all broadband technologies that meet the BEAD performance requirements in order to arrive at the most cost-effective solution. Within the next month, states must reevaluate network designs and reassess which technologies are best suited to reach unserved and underserved areas quickly and sustainably.

It’s an enormous policy shift, and it means that technologies once considered secondary or tertiary are now firmly in the running. Among others, these include unlicensed fixed wireless, which uses radio frequencies that don’t require government-issued licenses to deliver broadband over short to medium distances; LEO satellites, which provide internet access via constellations of satellites orbiting a few hundred kilometers above the Earth, and Free Space Optics (FSO), which transmits data using tightly focused beams of light between two fixed points. And with cost-efficiency and speed of deployment now front and center, these models of delivery are being reexamined not as fringe solutions, but as central to achieving BEAD’s middle mile goals.

Wireless Optical Communication: A New Generation of FSO

The phrase “bridging the middle mile” is a useful metaphor, but it does summon imagery of physical, tangible bridges that can be built and maintained. In the case of fiber cabling, this metaphor works. But what if instead of having a bridge in the physical world, with all the complications that come with building and maintaining