Where is the All-IP Network?

By: Jesse Cryderman

For many years now, telecom industry pundits have heralded the all-IP network of the future with messianic fervor. The one-network-to-rule-all-networks promises to flatten all competing transfer

protocols and standards into a single, packet-based passageway that is separate from the access technology. Its foretold gifts will eviscerate expenses and create ubiquitous service experiences

across all platforms.

For many years now, telecom industry pundits have heralded the all-IP network of the future with messianic fervor. The one-network-to-rule-all-networks promises to flatten all competing transfer

protocols and standards into a single, packet-based passageway that is separate from the access technology. Its foretold gifts will eviscerate expenses and create ubiquitous service experiences

across all platforms.

There's only one problem: it's still not here. Are we waiting for a fairy tale, or is the Next-Generation Network (NGN) any closer today than it has been in the past? With the rapid rollout of LTE networks, the promise of VoLTE, and the move to DOCSIS 3.0 in cable, at first glance the answer seems to be yes, we're are a lot closer than it might appear. However, there are still significant technical hurdles to be cleared before all networks are speaking the same language.

What is All-IP?

An all-IP network is simply a packet-based network in which all data is transferred the same way and independent of the access or transport technology. Industry parlance these days trends toward next generation networks, or NGN to describe the all-IP network. Here's how the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) defines NGN:

“A Next Generation Network (NGN) is a packet-based network able to provide services, including telecommunication services, and able to make use of multiple broadband, QoS-enabled transport technologies and in which service-related functions are independent from underlying transport-related technologies. It offers unrestricted access by users to different service providers. It supports generalized mobility which will allow consistent and ubiquitous provision of services to users.”

From this definition, it becomes apparent that there are several differences that must be addressed, compared to the numerous disparate networks of today. In the core, transport technologies must be condensed, meaning voice service must move from circuit-switched to VoIP, and legacy technologies such as frame relay (ISDN) must be migrated to all-IP. Similarly in the wired network, voice switching infrastructure (PTSN) must be eliminated and VoIP must be integrated into DSLAMs (digital subscriber line access multiplexers). And in the cable access network, a migration to PacketCable standards, which enable VoIP and SIP services, must occur.

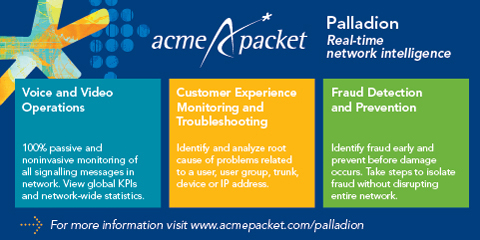

This network convergence is already happening, but the end product isn't going to be one giant network, like Skynet from the Terminator movies. Instead it will be multiple providers that

create the new network, "loosely federated with each other to trade traffic," explains Andy Ory, CEO of Acme Packet. It's much like the electron cloud that makes up today's model of the atom.

Does this model offer considerable advantages?